What do we mean when we say “Food System”?

Consider where your most recent meal came from. Where did the ingredients originate? What resources went into growing them? How were they processed? Who and where were they purchased from? And how many miles did they travel before landing on your plate? Given how essential food is to our everyday lives, it might strike you as strange that most of us would not be able to answer many of these questions in detail. The answers to these questions are what make up the “food system''.

More formally, the food system can be thought of as organized around a few major themes: staple crops, crop production, food processing and distribution, food consumption and cultures, and food waste.1 In this post, we’ll be giving a broad overview of the US food system as a primer for more in-depth topics in the weeks to come. There’s gonna be a fair bit of content coming up… so strap in!

An Overview of the US Food System

I. Staple Crops

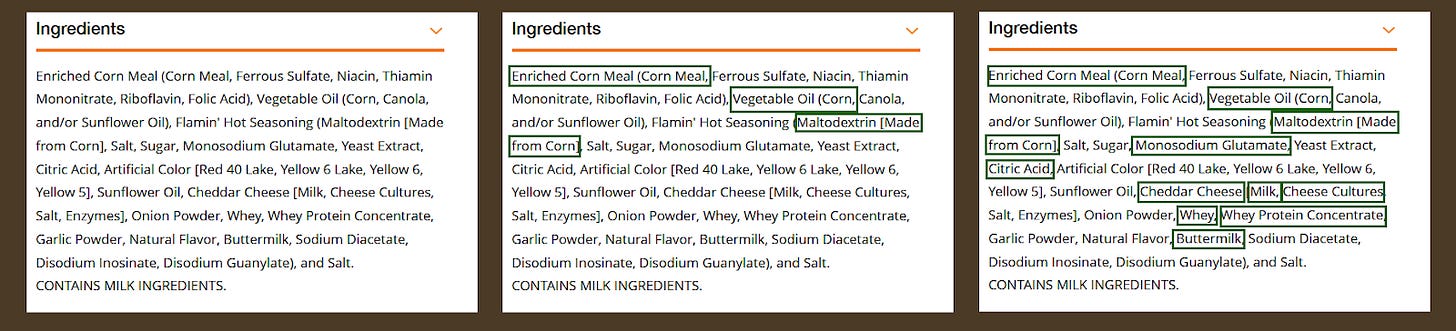

In the US, the food system is centered around corn and soy, but especially corn. Corn is, by far, the prevailing staple crop of the American food system, making up nearly 75% of total crop production in the US in a given year. In the 5 year period from 2015-2019, corn production averaged 14 billion bushels a year, more than tripling the next highest yield crop, soy, which sat at 4 billion bushels a year.2 What do we do with all this corn? Corn and corn-derived food products are a major component in many of our foods, especially processed foods. Take a look at a bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. The ingredients list may seem fairly varied, but a closer inspection reveals that most of what you are eating is just creatively rearranged corn, especially considering that ingredients are listed in descending order of abundance3:

However, even though so much corn is grown, very little of it is actually directly consumed by us. According to a 2019 USDA post on corn production, only roughly a third of the corn produced by the US is used directly as food for humans.4 Indeed, the vast majority of corn we grow was never meant for direct human consumption. Instead, the type of corn that is most commonly grown is known as “Number 2” corn, a starch-packed corn variety that is viewed as a commodity to be used as an industrial raw material (more on this in section III). The majority of the “Number 2” corn we produce is either converted into ethanol, processed into other food ingredients, or used as animal feed for pigs, chicken, cows, and even fish. Corn derivatives are also found in many non-food products, including many packaging materials, some diapers, and even some plastics.5

II. Crop Production

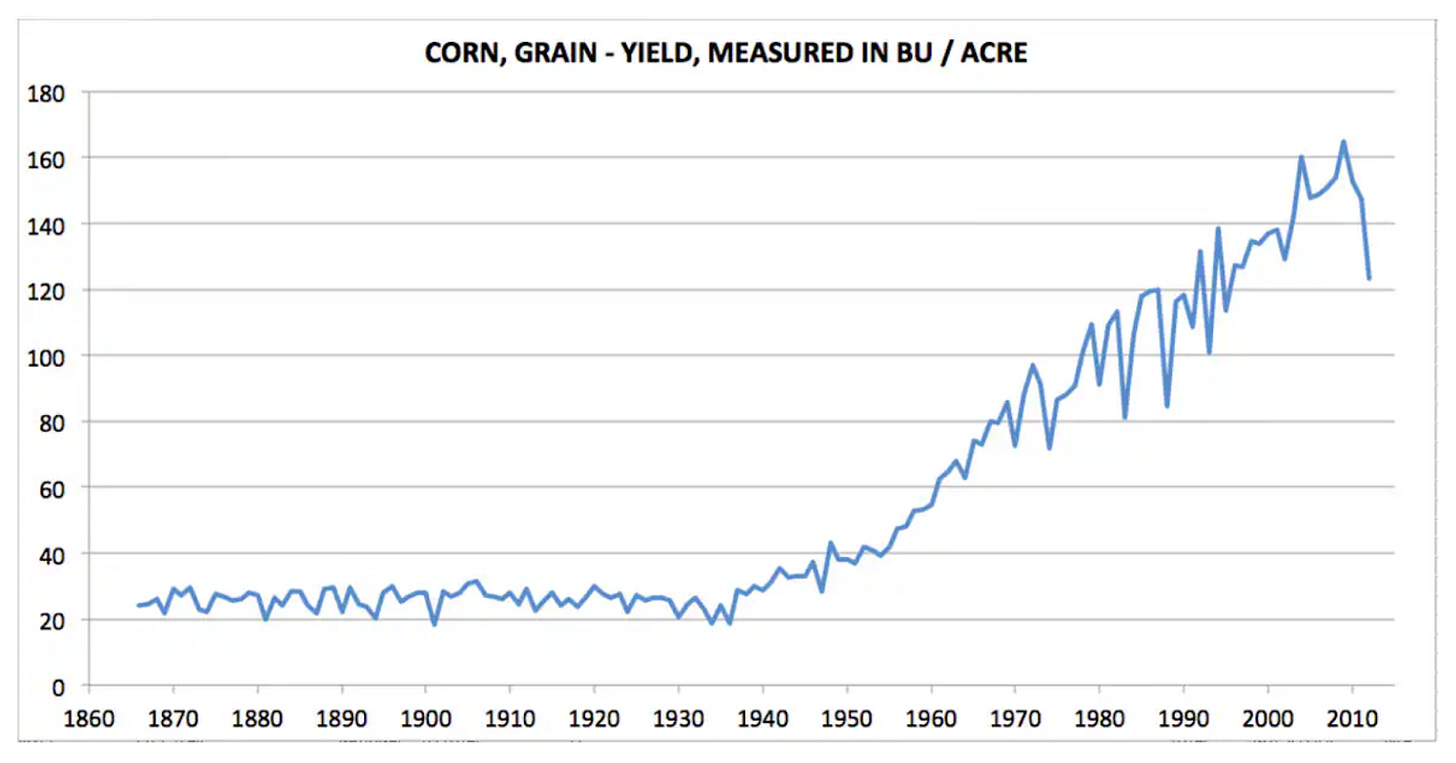

Okay… so we grow a lot of corn (and soy), but how do we do it? Most corn production occurs in a fairly concentrated area of the US known as the corn belt. In fact, Iowa and Illinois alone — the two top corn-producing states — are responsible for roughly a third of all corn grown in the US.6 The massive farming operations found in the corn belt are known as mono-cultures since only one type of crop is being grown at a time. This focus on growing massive fields of corn began in the mid-1900s and has rapidly accelerated due to two developments. The first was the introduction of various technologies such as specialized farming equipment, crop genetics, and growing techniques. These technological advancements have enabled farmers to continuously boost their yields and produce healthier corn, leading to an explosion in the bushels per acre that farmers can grow.7 However, these new technologies did not come without cost. In his book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Michael Pollan estimates that if we were to consider all the fossil fuel inputs needed to produce both the fertilizers and pesticides used to grow corn as well as power the machines needed to seed and harvest the crop, more than a calorie of energy is invested to create a single calorie in corn form.

Secondly, Great Depression era policies continue to bolster corn production via subsidies. The original intent of these subsidies was to provide a government safety net for farmers — the federal government agreed to purchase all corn not sold through the regular market at a set price. In turn, this would at once maintain a stable number of farmers while supposedly guaranteeing a steady and affordable supply of food for the American people. Without these policies, the number of farmers, and thus the staple crop yield, would vary with economic and environmental cycles, leading to unstable fluctuations in the price and supply of food.8 These subsidies (along with many other policies) would eventually be rolled-up into the Farm Bill, a sprawling piece of omnibus legislation that we’ll (probably) talk more about later. In short, the message that these agricultural subsidies have sent to farmers is this: grow as much corn (and wheat, and soybeans) as you can, and the US government will ensure that you are paid for any crops you produce.

Though this system has succeeded in boosting yields, decreasing prices, and increasing the overall efficiency of corn production, it isn’t without its fair share of issues. For one, as mentioned earlier, large-scale monocultures typically require fossil fuels as inputs for farm equipment as well as synthetic fertilizers. Fertilizers and pesticides used on these farms can also lead to ecosystem degradation when excess nutrients leach out of farmlands in the form of rainwater runoff. In addition, though farm subsidies were originally put in place with the intention of protecting the livelihoods of farming families, large agricultural corporations have found their way into politics, shifting the policy landscape. In recent decades, agricultural policies have actually neglected farming communities, instead optimizing for ever-higher yields at the lowest possible cost.

III. Food Production and Distribution

Almost all foods are processed in some way before being presented to consumers for sale. Even most fruits and vegetables are processed at some kind of sorting and washing facility before reaching a consumer's hands. However, produce and fresh foods account for only a small percentage of the average American diet. The majority of the American diet is dominated by packaged and processed foods with some recent estimates placing these foods at nearly 70% of the average American’s yearly diet.9 Processed foods are not necessarily bad categorically, but most contain high amounts of fat, sugar, and sodium relative to other nutrients. In addition, the added steps needed to extract and repurpose food ingredients in highly processed foods are energy-intensive and are typically inefficient. Pollan estimates that roughly 10 calories worth of fossil fuels are burned to produce just a single calorie worth of processed food.10 On top of all of this, pollution related to food packaging is also a big problem. Most food packaging is single-use and not meant for recycling, and even those that are often aren’t recycled.11 Plus, plastic recycling itself is already a pretty big mess, but that’s a topic for another post.

Like every other privatized industry providing essential goods and services to a captive audience, the US food processing industry has become dominated by a few large corporations. These large companies occupy an intermediate position between food producers and food consumers—buying animals and produce from farmers before processing, packaging, and provisioning food and food products to distributors and consumers. Take the beef industry for example. In 2019, the top 4 meat packing companies were estimated to control around 85% of the domestic beef market.12 Ordinarily, reasonable monitors of market consolidation would start ringing alarm bells once the top 4 companies control over 40% of a market. Unfortunately, the efficacy of our regulatory institutions has been greatly watered down—allowing agribusiness to operate as a state-sanctioned oligopoly. This concentration of market power is problematic as it gives these large intermediary corporations a lot of control over both farmers’ earnings and retail prices. Such high concentration also presents supply chain security issues, which have become more apparent during the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, this consolidation is hidden from the average consumer through a fog of brand names and product variations. Though we may see a sea of options when strolling through a typical grocery store, in reality, most brand labels are all owned by the same parent companies. General Mills lists some 50 different brands under their ownership on their official website. Similarly, Kellogg’s official website lists nearly 40 brands under their umbrella.13 14

This centralization of food processing necessitates a vast, interconnected web of distribution networks as well. Just within the US, food may need to travel across the country before landing on your plate. It is estimated that in the US, most food travels anywhere between 1,300 to 1,500 miles to reach consumers.15 On a global scale, food products are transported over even greater distances, whether across continents or overseas. Consumers certainly benefit from these vast food distribution networks. Economies of scale and regional differences in regulations allow food distributors to present cheaper prices to consumers while maintaining high-profit margins. In addition, the globalization of the food system allows consumers to have year-round access to foods that may otherwise be out of season locally.

However, these food distribution networks aren’t without their costs. “Food miles” was a term coined in the 1990s to describe the carbon impacts of long-distance food transportation. The distances traveled as well as modes of transportation all factor into the food mile impact of our foods. However, the question of whether locally produced foods are better in terms of their food mile emissions is complicated. While the carbon impacts of long-distance transport are relevant, it is typically more efficient than local distribution networks per unit of food due to the significantly higher capacity of aircraft and freight vessels. In addition, foods grown seasonally in distant locations have a much smaller carbon impact than foods otherwise grown in greenhouses more locally.16 17

This is not to say that there aren’t many benefits to supporting smaller, more local food systems. There are many other factors to consider outside of food miles when discussing local vs. global foods. For one, these local food systems encourage greater connection to seasonal foods, lessening our dependence on global systems to cater out-of-season produce year-round. Local food systems could also provide greater resilience to shocks that would disrupt larger, more centralized systems — the effects of which we saw during the recent pandemic. Finally, we would have much more power to steer local food systems towards sustainability and equity than we have over our current, highly-globalized food system.

IV. Food Cultures and Consumption

Food cultures and patterns of consumption are heavily influenced by which foods are most visible and easily available. In the US, food cultures often incorporate both regional and ethnic food traditions while consumption patterns largely reflect the prevalence of corn-based products. What foods we view as healthy, desirable, or even edible, are often informed by our food cultures. American food culture places a premium on making food appear aesthetically pleasing and clean, evidenced by the time and effort many processed food manufacturers spend in designing how their products are packaged. This also carries over into our produce, as many food distributors set strict standards on the size and visual appearance of the produce they buy/sell. This leads to uniform expectations from consumers on what food should look like, which in turn shapes our ideas regarding food quality, safety, and taste. For example, if a fruit or vegetable looks bruised or otherwise doesn’t conform to our aesthetic expectations, we may consider it inedible, though it may be perfectly safe to eat. In addition, the focus on presentation can leave consumers with a flawed understanding of important concepts like food safety and the natural appearance of fruits and vegetables.

Another trait of US food culture is an emphasis on presenting consumers with a deluge of options for very similar products. Potato chips, for example, have hundreds, if not thousands of variations for consumers to consider. Even something as simple as a tomato sauce may have dozens of variations in your local supermarket aisle. Different brands, flavors, cooking methods, and many other factors contribute to a dizzying array of products that no ordinary consumer could expect to meaningfully make sense of. Instead, most people learn to identify food products through the proxies of brand name recognition and familiarity.

In addition to aesthetics and variety, convenience is another pillar of US food culture. As discussed in the previous section, the global supply chain has resulted in a system in which most foods are available year-round. Commodified crops, complex food processing routes, and vast distribution networks have also distanced the average consumer from having a deeper understanding of their food. As a result, we expect food to be fast, cheap, and available while remaining ignorant of the environmental and human costs. Our obsession with cheap and fast food feeds into and perpetuates our current industrial food system while encouraging similar systems abroad, driving a feedback loop between unsustainable food systems and unsustainable food cultures.

The US also has one of the highest meat consumption rates per capita in the world. According to 2017 data, the average individual in the US consumes around 98 kg (~215 lbs) of meat every year.18 This aspect of US food consumption is especially damaging considering that animal agriculture is one of the biggest agricultural sources of pollution and carbon emissions. Furthermore, with a large reliance on corn for animal feed, animal agriculture further perpetuates the current industrial food system. (More to come on animal agriculture, with a focus on beef, in future posts!)

V. Food Waste & Access

This brings us to the topics of food waste and food access–which, while not exactly two sides of the same coin, are inextricably linked under the current organization of our food system. At this point it's important to make something clear: we do not have a shortage of food in the United States (or the world). Humanity currently produces enough food (from a caloric requirement perspective) to adequately feed every living person and then some.19

So where does the food go if not to the mouths of the hungry? Well, as mentioned earlier, the majority of our agricultural yield is used to feed livestock, whose meat eventually ends up on a consumer’s plate. While this food is not technically wasted, converting plant food to meat is an extremely inefficient process that reduces the total amount of calories available to humans at large.

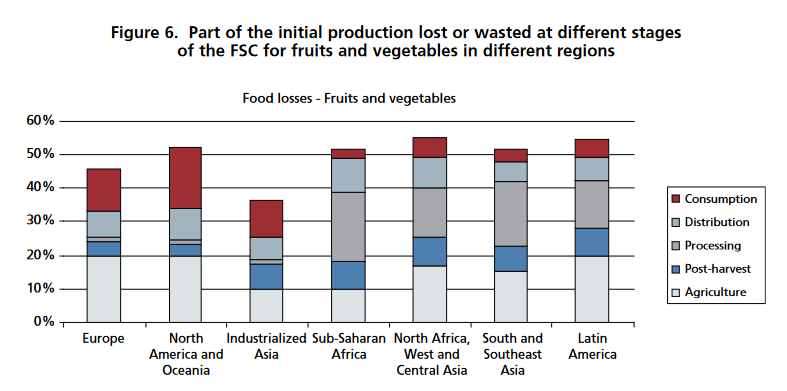

That’s not the only source of waste though. Food is actually wasted in the common sense of the word at every stage of the supply chain from harvest to consumption.20 21 A portion of crops are not harvested due to pest damage or aesthetic defects. Produce that makes it out of the field can sustain further damage during the processing stage while being prepared for transport. Parts of the selected harvest can then degrade in transport due to issues with climate control and pests, or on the market shelf while waiting to be purchased. These potential sources of waste are exacerbated by the often extreme distances food travels from farm to table. Additionally, waste at the consumer level, especially in developed countries, is often one of the largest sources of food waste — consumers simply don’t eat everything they purchase. Finally, despite the relative ease and proven benefits of composting, municipal composting programs are rare in the United States. This results in a large volume of compostable food products being sent to the landfill instead, where they decompose and release large amounts of methane.22

As we’ve briefly illustrated, there are many ways for food to not end up in a human’s intestines. A lot of the potential waste occurs before food even makes its way to the consumer. But even if we circumvented these issues and all the food we produced did end up in the supermarket, there is an entirely separate issue of food access that can prevent people from getting the food they need. You’ve likely heard about the rising costs of essential commodities, and you may have even noticed higher prices while grocery shopping over the last few months (inflation going crazy frfr). The cost of staple foods, and the buying power of the average American compared to those costs, is a major factor that affects food access. Also, take a moment to consider the logistical challenges (or lack thereof) that you face when acquiring food. How far away is your nearest supermarket? Is that supermarket adequately stocked with affordable and healthy foods? And do those foods align with your dietary restrictions and ethnic food traditions? Do you make use of online grocery delivery services or meal delivery apps? How might food access change for you if you moved to a rural town, lost your job, or suddenly developed a severe allergy to corn or soy? Thinking through these questions can help you begin to understand the myriad factors influencing our ability to feed ourselves.

Unfortunately, despite being the wealthiest nation in the world and producing more than enough food to feed its citizens, the United States has a widespread food insecurity problem. According to the United Nations, “[a] person is food insecure when they lack regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life. This may be due to unavailability of food and/or lack of resources to obtain food.”23 In 2019, 10.5% of American households reported experiencing food insecurity. That figure jumped to 23% during the Covid-19 pandemic. Families with children experience food insecurity at even higher rates, with some estimates as high as 30% for 2020 and 2021.24 This is a massive share of the population—amounting to 14 million children—that do not get enough food to be considered healthy. As you might expect, this has a profound effect on their ability to grow and develop, do well in school, and find prosperity later in life. Finally, as with many of America’s societal ills, the impacts of food insecurity are not evenly distributed across race, geography, or socioeconomic status. People of color, especially Black, Latino, and Indigenous Americans, are many times more likely to be food insecure than their White neighbors. People living in rural communities are also more likely to face food insecurity than those living in urban and suburban areas.

You might be thinking — “What about food stamps and soup kitchens?” The short answer is that neither charity nor narrowly-scoped government programs can solve the problem of food access because food access is not just about food. It’s about the layout of our cities, the organization of our economy, and the ever-widening disparities between rich and poor, urban and rural. In a future post, we’ll dive deep into this issue and discuss the root causes and potential solutions in greater depth.

Where to from here?

By now you’re probably realizing that, while the current food system is efficient and pleasant for a lot of consumers, there are also major drawbacks that will become even more problematic for our species in the future. In our next series of posts, you can expect to start exploring some of these issues in greater depth, as well as reflecting on possible solutions. Here’s a (not necessarily exhaustive) list of topics we’ll try to cover:

Hunger — not a scarcity problem

Misalignment of business incentives with human interests

Environmental costs of industrial farming

Meat

What is “regenerative agriculture”?

What is “Food Sovereignty”?

Practical changes to try making in your own life

We know that we just threw a lot of information at you, and that this all might seem a bit hard to digest. Though there’s a lot to be desired from our current food system, the good news is that there are people cooking up creative solutions to combat the issues we currently face. We hope that you were able to learn something new, or at least get some additional food for thought.

Thank you for making it to the end of this post! As always, if you have any questions about this post or topics you’d like us to talk about in the future, feel free to leave a comment! Until next time, stay safe (人>U<) and stay strong ( ◡̀_◡́)ᕤ kings/queens/eating machines └[∵┌]└[ ∵ ]┘[┐∵]┘25

Michael Pollan — The Omnivore’s Dilemma - Chapter 2: The Farm

Michael Pollan — The Omnivore’s Dilemma - Chapter 5: The Processing Plant

This is great! You could do a whole post on just corn itself. There's so much to talk about in this space.

This is so thorough and well-researched. Thanks ecobaes : )

Question -- what can everyday consumers like us do to in response to some of these issues?